Punctuate : New Paintings by Jim Mooney

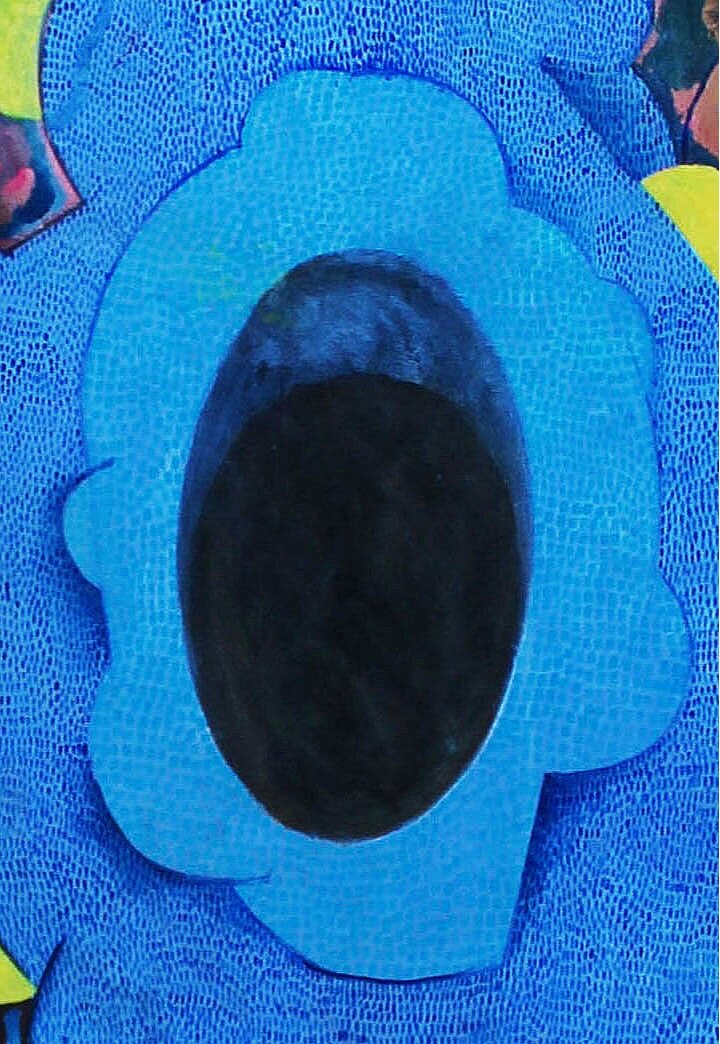

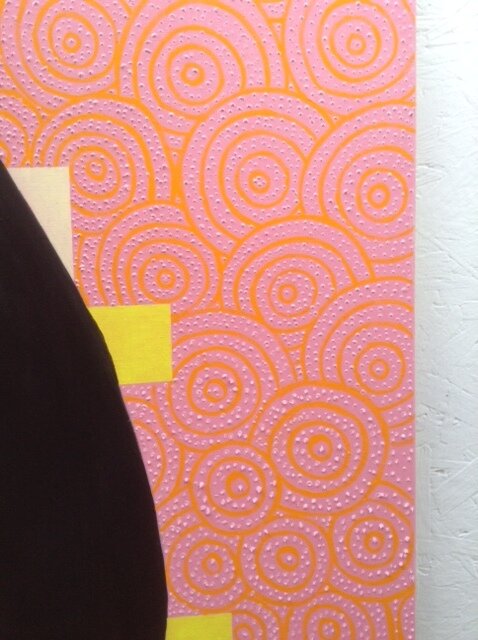

Jim Mooney BodyWithout Organs No.1, 2019, photograph courtesy of Ewan Weatherspoon

I talk to the trees, but they don’t listen to me. I talk to the stars but they never hear me.

Lyric from the Broadway musical-comedy Paint Your Wagon (Alan J. Lerner, 1951)

If any infidel lighted torches or worshipped trees, fountains or stones, or neglected to destroy them, he shall be found guilty of sacrilege.

The Second Council of Arles (Roman Catholic edict, 452 AD)

The mountains are great stone bells; they clang together like nuns. Who shushed the stars?

Annie Dillard, Teaching a Stone to Talk, 1982

I. Talking Paintings

I first encountered Jim Mooney’s painting “Body Without Organs No.1” this past summer at the 2019 Edinburgh Festival in the painting exhibition “Fully Awake”. I was performing at the opening of the exhibition and had arrived a few days earlier to see the space and check out the sound equipment. When I arrived the curators were busy hanging the show in four large painting galleries at the Edinburgh College of Art. I was directed towards a locked room where the sound equipment was stored. I passed through three galleries of paintings and as I approached the locked room I was stopped in my tracks by a painting whose pull on my peripheral vision forced me to turn and take a full look.

And there it was, a body without organs, a torso sized ovoid, its darkness blooming like the heart of a poppy dreaming of its own sleep, a shadow ghost floating in a pool of crimson red on a sea of hot pinks. At the cardinal points four bright yellow palm-sized dots appeared, partially eclipsed like blind spots pulling me in. I saw petrol spills of Prussian blue paint mixed with burnt umber seeping over the surface like clouds passing across the sun. Beneath the cloud surface another surface of concentric circles appeared, expanding like sound vibrations, surfacing ring shaped echoes of unheard words rising from the depths of language, as if the painting could speak.

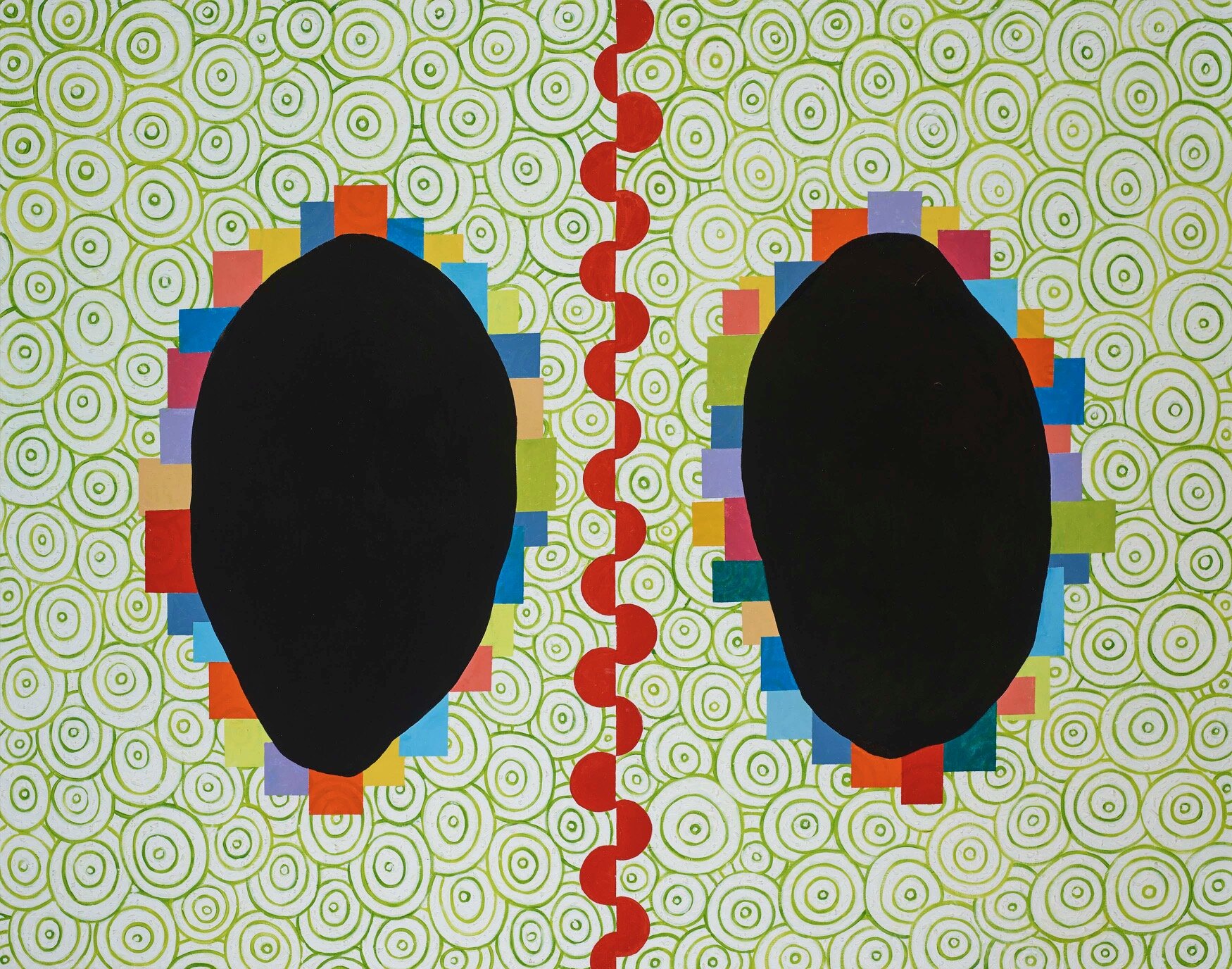

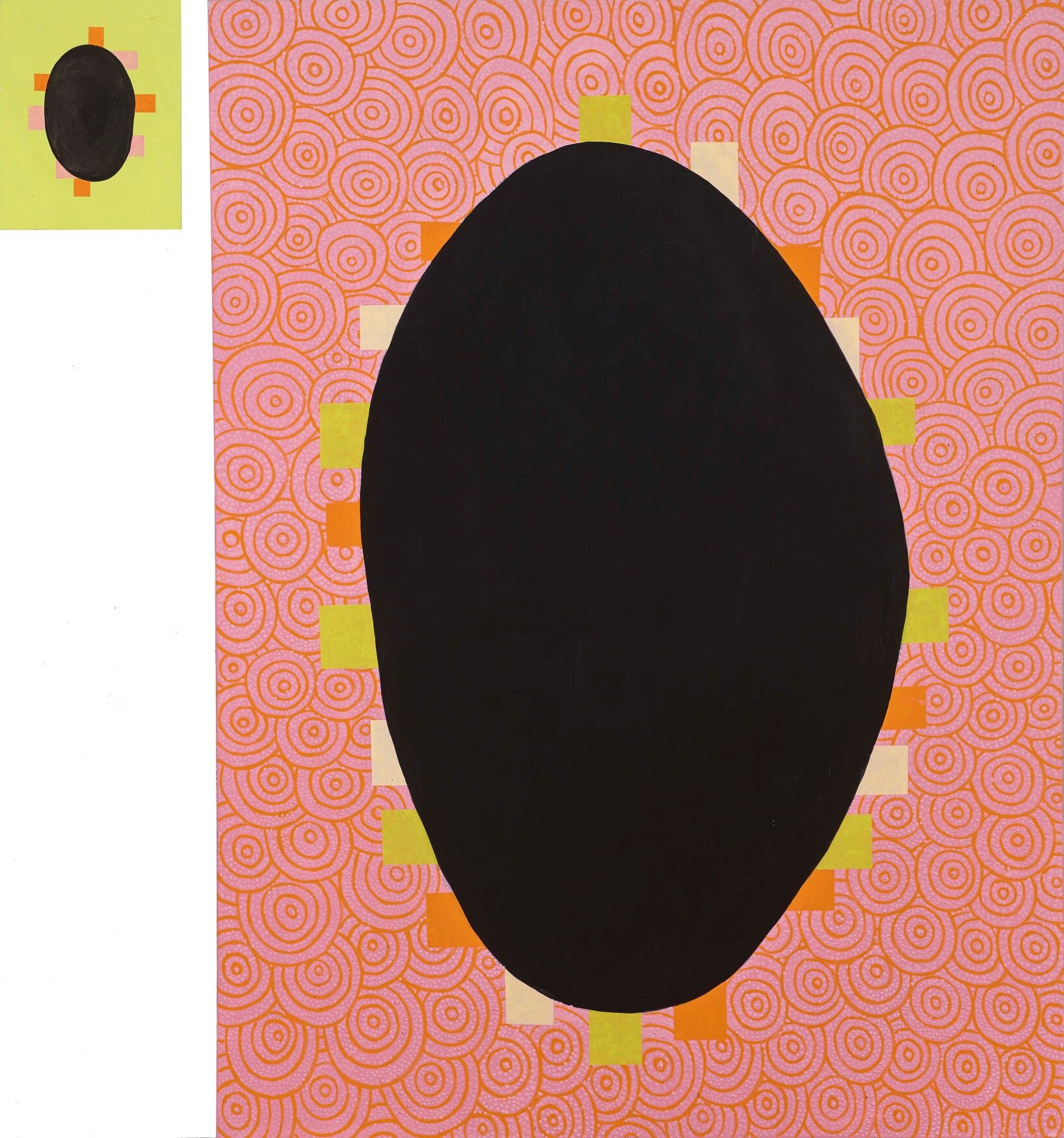

This is the thing about Jim Mooney’s paintings, they feel alive, and they speak to us, but how do these painting speak to us? We need only look to the title of the exhibition, “Punctuate” to be alerted to the artist’s intention that language and meaning, text and textures are organizing energies in this body of work. To punctuate is to add marks to a text in order to aid meaning. These marks; semi colons, commas, and full stops (to name a few) effect a pause, a space for sense to accumulate and for meaning to take place. In the exhibition, Mooney carefully places smaller related paintings throughout the galleries in order to puncture the space and to act as punctuation. But it is important to state that this exhibition is not about punctuation, much in the same way that these words you are presently reading are not about alphabetic letters; however, these letters are signs that communicate meaning such that ‘we see what they say’, thus “Punctuate” is a sign that points us towards, indeed is a point of entry into, the paintings themselves. I will return to points, punctums and dots in Mooney’s paintings, but first I want to consider the use of signs as a means of communication because communication provides an important key to these works.

II. Signs of Life

In her book ‘The Love of Painting’ (2018) the art critic Isabelle Graw begins by using semiotics in order to explore the use and effects of the communicative power of painting. In semiotics, the study of sign processes, a sign is anything that communicates meaning to the interpreter of the sign. Unlike linguistics, semiotics also includes the study of signs that are non-linguistic, such as analogy, metaphors, symbolism, symptoms, and allegory. It is why semiotics has proven to be such a useful tool for examining meaning across virtually any discipline; for example, medicine (how to read symptoms), anthropology (how to read rituals), computing (how to read code), criminology (how to read evidence), economics (how to read numbers). Isabelle Graw uses semiotics to read painting.

The 19th century American philosopher, mathematician and scientist Charles Sanders Pierce identified three categories of signs that are used in semiotics; 1) icon : is a stimulus pattern that has meaning; for example, a picture of an envelope on a computer or phone screen signifies the mail function, or a picture of a light bulb lighting up signifies the occurrence of a bright idea, 2) symbol : is an arbitrary sign whose meaning is relational and most often culturally specific; for example, the word ‘paint’ is not paint in and of itself but rather refers to something called paint, and 3) index is a sign that has a physical relationship with what it is signifying, it operates as evidence; for example, a footprint signifies a foot, dark clouds signify a storm, smoke signifies fire. According to Graw, it is specifically in painting where indexical signs predominate. It is the corporeal, material dimension of the painterly sign, the gesture and mark of paint that presents the viewer with traces of the presence of the absent artist. The effect of the indexical is the power of evidence. Where there is smoke there is fire, where there is a painting there is a painter, the author of the painting. Such is the power of the indexical connection between painting and painter that one need only think of a famous painting and the artist springs to mind; that is a Leonardo, this is a Frida Khalo. We put a definite article in front of the artist’s name when identifying a painting and in doing so we conflate the person with the thing, painter and painting (note that ‘painting’ is both a verb and a noun). This conflation of painter and painting, subject and object, confers a status on painting that Graw calls quasi subject. The quasi subject produces “imagined vital features such as liveliness, life force, subjectivity or en-soulment into dead matter”, this effect she calls vitalistic fantasies.

While Graw traces these vitalistic fantasies in painting back to the European Renaissance and the aesthetic ideal that figures and paintings ought to appear lively and animated, the idea of the transformation of the inanimate into the living, often at the hands of a talented artist, goes back thousands of years and can be found throughout the world. The historian Julian D’Huy performed a phylogenetic analysis on various iterations of Ovid’s Pygmalion (the myth of a sculpture that comes to life) and discovered that the Greek and Bara (Madagascar) myths likely split from the Berber (North Africa) story three to four thousand years ago.

III. Ghost-busting

Painting is an illusion, a piece of magic, so what you see is not what you see.

Phillip Guston

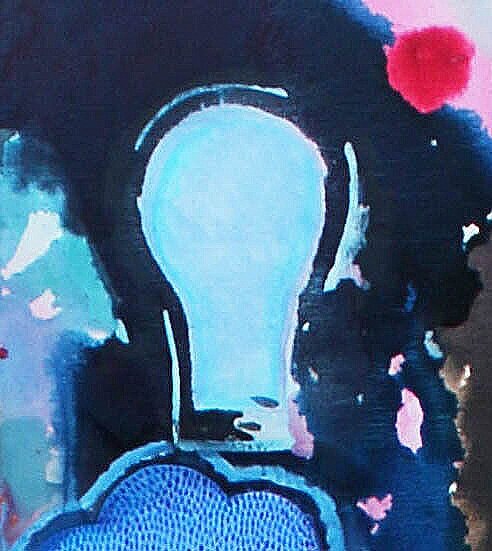

At the centre of Mooney’s painting ‘Apparition’ floats a large blue cloud, its surface embellished with dots. The cloud is outlined in ultramarine giving it a distinct animated character, a shape from a trippy cartoon. Above the cloud, another cartoonish shape, of what might be read as a head or a pale blue light bulb. Its thick dark outline is done in one continuous brush stroke, as if the paint stroke itself had lit the bulb, painting at the speed of light. It is funny and playful and alerts us to the ideas at play in this painting. In the centre of the cloud is a dark oval, unlike the other ovoids throughout the exhibition this oval shape is strict and symmetrical and suggests something man-made like a mirror, further emphasized by what appears to be the shadow of a head caught in the mirror’s reflection. Again I am reminded of Graw’s proposition on the indexicality of painting; that the physicality and materiality of painting signs evoke the ghost-like presence of its absent author. With the ghost-like shadow at the centre of Apparition, Mooney draws our attention to someone or something that is not there, he simultaneously exaggerates and mocks an authorial presence in painting, the subject that is both there and not-there, or as Graw calls it, the quasi-subject. The title ‘Apparition’ is doubly indexical, not only does it point to the ghost-like presence of the absent author, but it also points to an image that is effectively smoke and mirror, as if to say that painting is an illusion and Apparition is a ghost-busting myth of a painting.

There is something oddly comic about Apparition, with its bold shadows and outlines, Beano cartoon colours, bubble-gum pink polka dots and the absurdity of a shadow trying to catch a glimpse of itself in a mirror floating in a sea of hallucinatory abstraction. This comic cartoon styling and painting seriousness, reminds me of the late work of the American painter Philip Guston (1913-1980), who after establishing himself as a serious abstract expressionist painter and academic, left New York City in 1967 and moved upstate. Frustrated by the purity of abstraction in a world that was messy and complex his practice underwent a radical change in style and content, making paintings that were full of vulgar cartoon figures, in plastic pinks and shitty browns, that were both a comic and serious take on the subject of the painter and painting itself. As an aside, I note that in the Wikipedia entry for Philip Guston his style is listed as: “cartoon, abstract”, a rather apt stylistic description of Apparition.

The significance of cartoon as a style in painting is bound to animation, the state of being animated from the Latin root anima meaning breath, it signifies what is living and breathing and gives us the word animal. Animation in this sense is what we know as liveliness. It is this liveliness, this vitality; that Isabelle Graw returns to throughout The Love of Painting.

Mooney deploys a full range of painterly devices that evoke animation. He does this in the full knowledge that painting is an act of animation in and of itself. The paintings in Punctuate form a shifting, hallucinatory mapping of liveliness and presence. The repetition of motifs, and shifts in scale provide a rhythm, surfaces shimmer, colours vibrate, dots, circles and spots pulsate, and rings radiate.

IV. Dots, Spots and Points

There is a mobility of the retina, a chromatic circle we traverse, and which is animated ('a living circle') according to a movement of eternal opposition capable of animating images with a molten rapidity whose lasting effect is conserved in colours.

Eric Alliez, The Brain-Eye

Mooney paints concentric circles that pulse like sound vibrations. He tells me that he most often paints the circles in yellow ochre deep and that they are meant to inject an Orphic/oneiric element, indeed these are animated soundings, echoes from oracles and dreams. He covers sections of surface with tiny points of paint applied using syringes as a sticky impasto or with dry brush, creating goose bumps of paint; and here I must fully quote Mooney’s own description of these pimples of paint so vivid and knowing of the effects they create: “…suppurating surfaces; raised nipples of paint that capture light in order to animate areas of surface. These methods create a shimmering, bristling, unstable and mobile surface of points (redolent of light sparkling on the surface of the sea) and produce a slight bas-relief surface that shifts and glints casting subtle shadows that engender a slightly wavering light. This has the effect of either creating a visual field that bristles with desire or serves to highlight selected areas of low-level visual vibration or hum. Both serve to direct the gaze and in fact could be said to return our gaze. Glistening.”

V. What about you?

And the unseen eyebeam crossed, for the roses

Had the look of flowers that are looked at.

T.S. Eliot, Burnt Norton

A picture can only appear alive if there is a viewer ready to project a liveness onto it.

Isabella Graw, The Love of Painting

Nothing matters in painting without you, the viewer. Just as an actor stands before us and says without speaking ‘look at me’, we stand before a painting and it asks us to see. At the centre of the painting Monstrance we see a rosy pink oval, and like the oval in Apparition its shape is strict and symmetrical and suggests something man-made like a mirror, but here the mirror is covered in tiny glossy dots. The same dots that Mooney has said “serve to direct the gaze and in fact could be said to return our gaze. Glistening”.

Monstrance, as with all the titles in the exhibition, is a sign that points to the heart of the painting. A monstrance, meaning to show, from the Latin monstrare, is a ceremonial object designed to display a sacred item. It features a round glass vessel encircled by radiant beams resembling the sun. And indeed we see such a figure in the painting Monstrance, albeit in playful colours and cartoon stylings. The bright blue radiating beams appear to pierce the dark spots that dot the painting, like light piercing retinas or blind spots. In fact the bright pink central oval with its glistening dots floats on a dark red bed of Alizarin crimson, the contrast of colours causing a retinal burn of the image. A glowing mis-en-abyme of an image reflecting itself; Monstrance shows us, the viewer, caught as a gaze in painting, not as a reflection but glimpsed in the flash of radiating light, a virtual projection. We pass through paintings as a body without organs aligned with other bodies without organs. You, painting and painter, like three celestial bodies of a solar eclipse, we appear, shadowed and radiant alike.