Wild Relatives

The film Wild Relatives (2018, 64 minutes) by the artist Jumana Manna begins underground in the dark recesses of a mine where a mining machine is extracting coal from a seam. The soundtrack is part machinic hum part heartbeat. As the narration begins the scene shifts, we are now looking skywards through leaves and stalks in what can best be described as a ‘seeds-eye-view’ from the ground up. The ‘wild relatives’ of the title are seeds for grains fundamental to crop diversity. In the film the seeds drive the narrative, they possess what the philosopher Jane Bennett describes as “thing- power”, the inherent power of non-human entities to exert influence and participate in shaping the world. It is this vital determinism that infuses Wild Relatives with its liveliness and creativity. Everything is enlivened in the film, the seeds, the soil, the wind, the landscape.

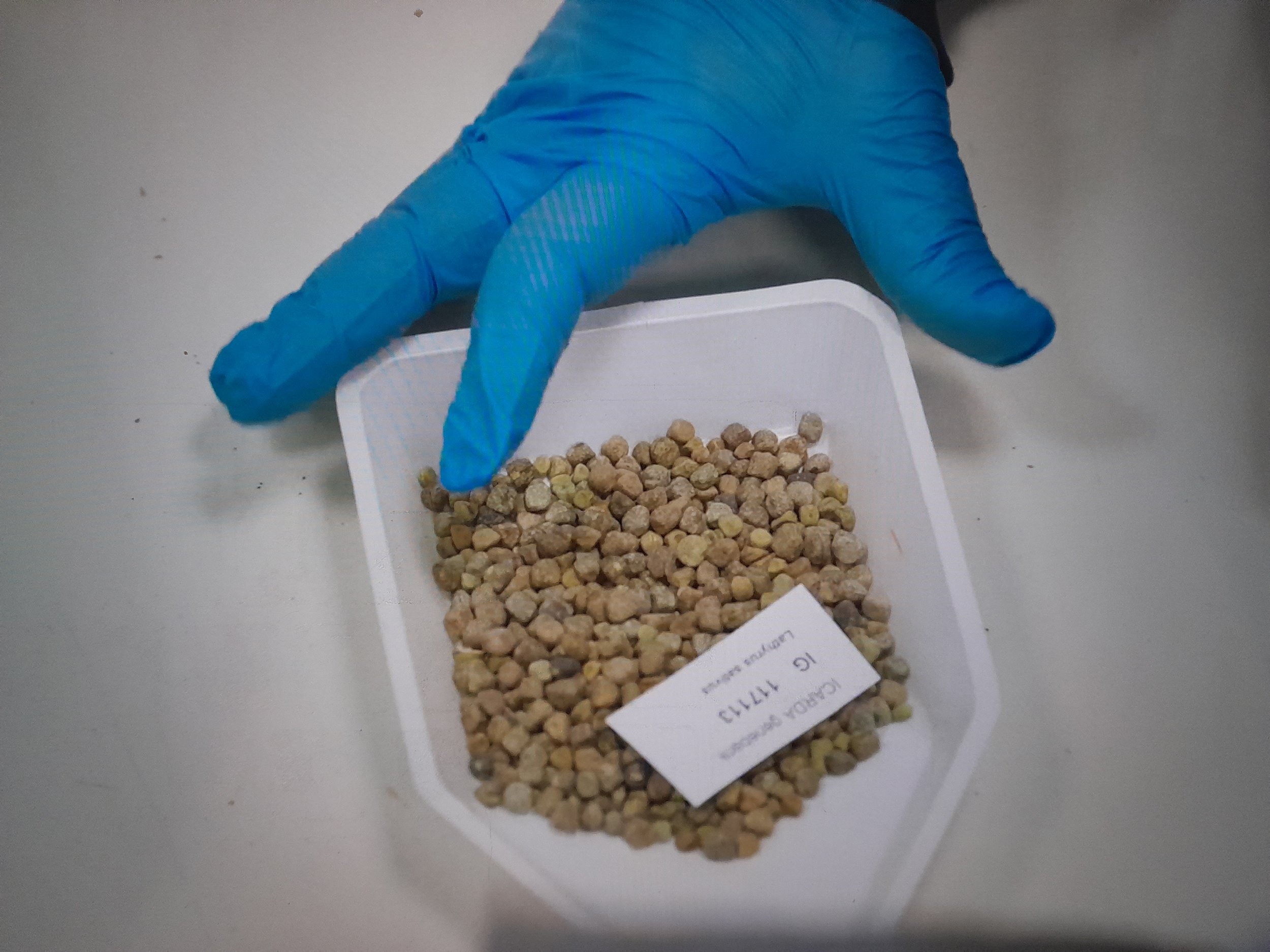

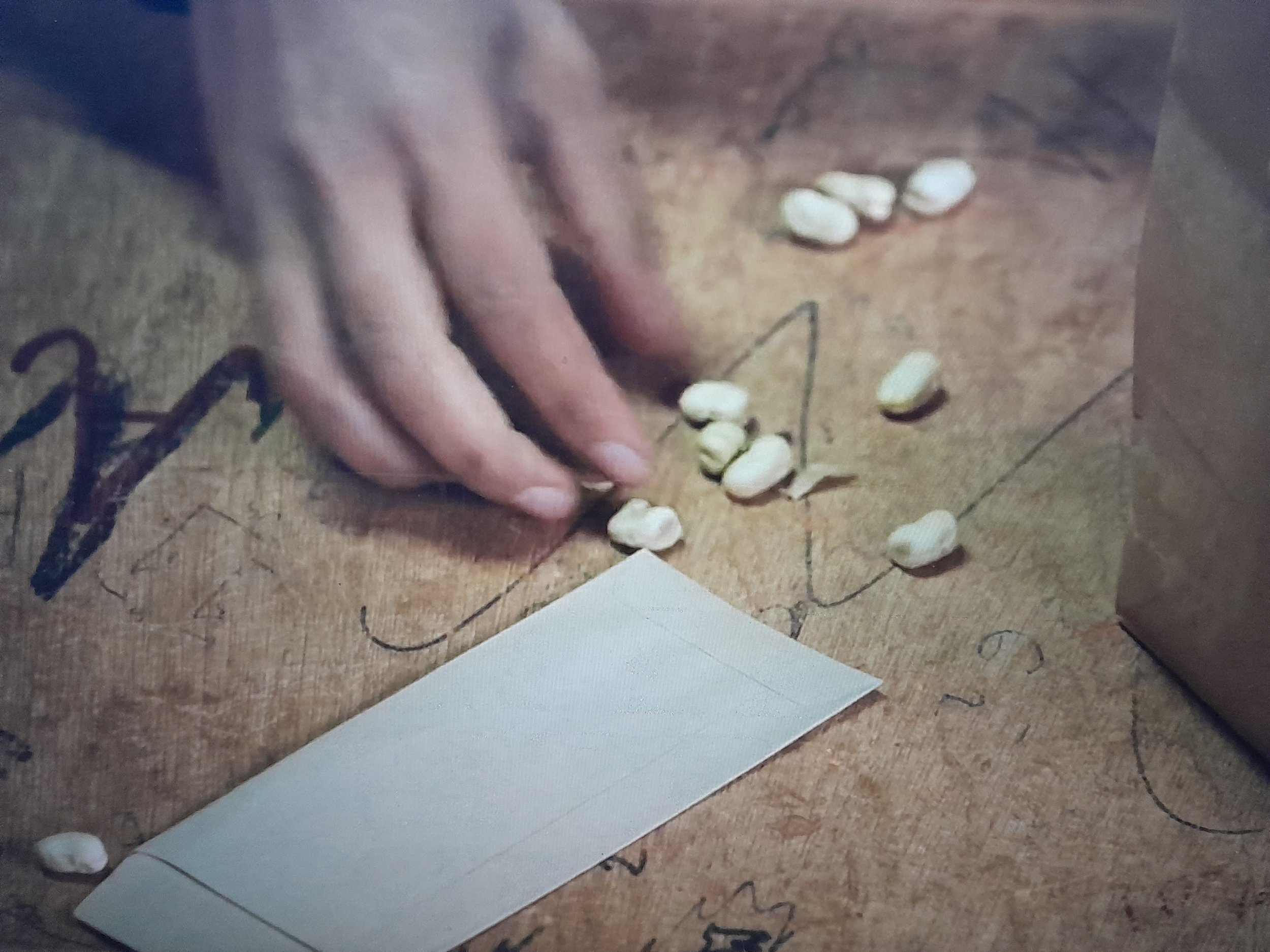

The film is an account of 12 months in the lives of people from Lebanon, Syria and Norway as it follows the transaction of seeds lost in an Aleppo agricultural research centre which had to be closed due to the Syrian war. The replacement seeds are drawn from the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway deep below the permafrost in an abandoned coal mine on an island in the Arctic Ocean. These seeds are then planted in Lebanon by young female Syrian refugees and the seeds from these plants are then gathered and sent back to Svalbard to replace the original seeds taken from the seed bank. We watch as the seeds are planted, rained upon, grow, are harvested, collected, sorted, transported, labelled, and stored through the hands of farmers, refugees, scientists, government employees, volunteers and labourers. Through the seed transactions and transformations the film reveals the entanglement and interdependence between human and non-human entites between state and individual, and industrial and organic approaches to seed saving, climate change and biodiversity.

Whether in a laboratory or a landscape the director of photography Marte Vold carefully composes scenes that tease out geometric patterning; rows of wheat, stacks of shelves, circles of test tubes. Long shots that place the human into the landscape are interspersed with close-ups of hands. Hands become actors interfacing between action and object, they are, if you like, the digital interface par excellence. As if taking inspiration from seed growth itself the film editing by Katrin Ebersohn gives the film the pace of a slow, graceful cyclical pattern. From the global to the microscopic, individuals, institutions, and governments the film affects an expanded understanding of subject and object, agency and causality placing politics at our fingertips.